Technological Urbanism as a Military Weapon

I am a young architect and researcher based in Armenia and Luxembourg. I studied at the University of Luxembourg and obtained my master's in 2023. My master's thesis tackled the questions of war and architecture, which received an exceptional assessment.

My interests include socio-spatial issues of urban development, such as housing, land, and ownership, which have distinctive patterns everywhere, the questions of public space and how those disciplines integrate into the environmental discourse. However, my interest revolves more around war and architecture now and how architects should operate within spaces outside the regular legal system. Spaces where the understanding of margin is determined based on secret agreements within certain transnational governmental bodies or organisations without considering people's rights living there. I am also highly inquisitive about art and photography and how these domains can incorporate into architectural practice and research.

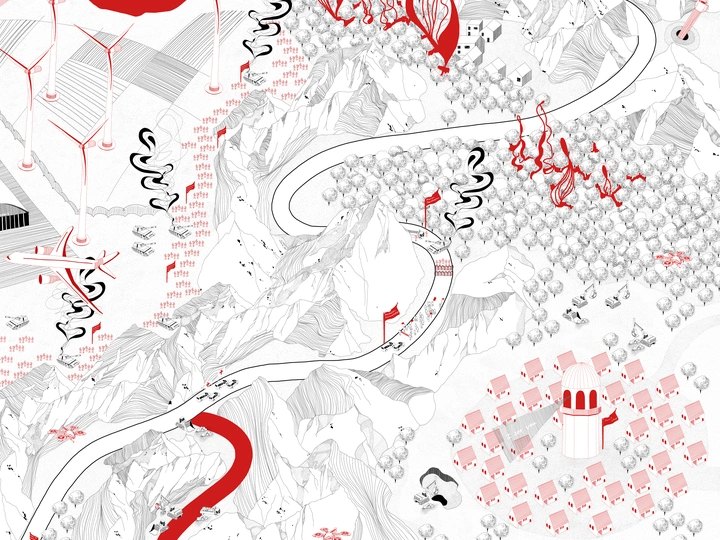

War destroys cities and landscapes to the point of unrecognition; it leaves people with trauma and loss. The shape of cities drastically changes and adapts to specific situations that war dictates. Everyone knows and sees the destructive capacities of war, but architecture and construction could also have destructive capacities. My research looks at how throughout and after the war, architecture, reconstruction of new settlements (smart villages), technology, and infrastructure have been used as war weapons in claiming and colonising territories through investigations of real-life examples in the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh Republic) – a disputed, unrecognised de facto republic in the South Caucasus inhabited by mainly ethnic Armenians, that has been for centuries a centre of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

How can we distinguish revitalisation from spatial architectural solutions disguised as military tools? With my research, I took the political laws and maps produced by different actors and used them as tools to unpack this question. In this research, mapping becomes the instrument for repairing the territory. It questions the news and media-produced political representation of maps: and proposes another way of seeing them, rather than acknowledging maps as a 2D tool or scheme to give a piece of technical or political-strategic information. What could be another way of making maps in the context of war? One of the produced two-sided maps brings to the surface the context of the issue and highlights the suppressed voices. The other two-sided map shows how war and after-war spatial processes affect the region from the surface and underneath the ground, creating a human and environmental catastrophe and turning the territory into territorial prison for testing. In my proposal, I used maps as a form to claim the rights of the people affected by it and urge for recognition and response to this destructive problem in different parts of the world.