Ewa Effiom: In Progress

It’s not controversial to say that we find ourselves in unprecedented times.

I hope you’ll forgive this platitude which, I’m sure, reminds us all of 2020 when it reached its most intolerable pitch, when confined to the four walls of our respective homes, we were unsure of what the future would bring. Revolution was upon us! Surely we could never return to working from an office five days a week, neglect key workers, or forget the restorative power of solidarity in times of need? As it turns out, inflection points are easier to name than to sustain and history, as ever, has a way of reasserting itself. Yet some traces of that rupture remain.

Even architecture, a discipline that isn’t the nimblest of fields, was again beginning to engage with futures recognising that the established order was no longer tenable. This reckoning coincided with the realisation that the very systems that Architecture serves have brought the planet to crisis. Design and by extension architecture, is hard to dissociate from planetary condition, as is its complicity in the ecological, social and political crises of modernity. Architecture is implicated in the polycrisis; in fact, I believe that it is this very polycrisis that underpins its existential anxiety.

Architecture today, exists as a mechanism for the absorption of capitalist surplus which is in direct opposition to ecological imperatives. It has become the realm of frenzied consumerism available only to those who can afford it. The urban planner, Ananya Roy reminds us that cities are not just sites of density but of inequality shaped by global flows of capital that displace as much as they connect (1). In fact, the sociologist, Saskia Sassen’s idea of “expulsions” helps us see architecture’s complicity in the violence of urbanisation (2). This flux is a result of markets’ speculative impulse that displaces lower income residents and informal economies in favour of capital.

Despite its speculative nature, architecture has a complicated relationship with the future. It presents itself as a driver of progress but history shows us that it has often left the ruins of communities, of land and of nature in its wake. Sustainability has resulted in both material change and performative actions. Offering a permission structure, spurred on by the neoliberal order, as it encompasses both genuinely environmentally conscious community innovations and eco lodges for the wealthy. Architects’ carbon-laden professional service harbours no malicious intent, per se, but it is further from a neutral entity than it would have you think. There are too few examples of the sustainable architecture for the masses because we haven’t dared to intentionally decide what the world might look like if as Sheila O’Donnell says people understood that we were: “…building for them, not despite them.” (3) Instead we hide behind deference to markets with the delusion of its neutrality which offers a convenient alibi. Technology is too often brandished as the solution with little consideration for whose interests it serves or the world that it might build. The post-industrial conviction that technology would propel us into the future has instead bound us to a pragmatic superficiality in the face of our own demise.

Architecture’s strategic apathy gives us a troubling insight into how we might callously and obliviously meet our future. A future which has travelled back through time to haunt us.

Hauntology, Jacques Derrida’s play on the words haunting and ontology, speaks of the past’s persistence in the present and the feeling of being haunted by the unfulfilled promises of futures lost (4). This idea emerged in the aftermath of the Soviet dissolution and the alleged associated disappearance of history.

Mark Fisher, the critic and cultural theorist, revived the concept of hauntology when he observed the inertia of electronic music in the mid-2000s (5). A genre that had once reliably evoked the future, from the aftermath of WWII through to the 1990s, sounded trapped in an endless loop of repetition, an uncanny echo of the philosopher, Franco Berardi’s claim that “we are living after the future.” (6) To borrow from Owen Hatherley: the demolition of brutalist buildings provides another a glaring image that evokes the failure of the anticipated future to arrive (7).

Fisher diagnosed a deterioration of the social imagination and an incapacity to conceive of a materially different world. In this context politics and economics are reduced to administering the established order, creating a regressional custodial loop transforming them into instruments of maintenance that endlessly reproduce the present. While the political scientist, Francis Fukuyama, called this the “end of history,” (8) the critic, Frederic Jameson described the inability to find adequate forms in the present much less anticipate wholly new futures as the cultural logic of late capitalism (9).

The limitation of imagination is perhaps the quietest violence of our age, yet its consequences are clear as fascistic governments emerge all over the world, rewriting our pasts to determine our futures. Here, imagination becomes a form of resistance.

Frantz Fanon, the political philosopher and psychiatrist, urged us to ‘introduce invention into existence;’ (10) the historian Robin D. G. Kelley, claims in fact that ‘the map to a new world is in the imagination.’ (11) Together they suggest that invention and imagination are not luxuries but tools for survival. It is through these that utopia takes shape, transforming utopia from a distant ideal into a politics of possibility. The philosopher, Ernst Bloch, argued that utopia is not an escapist fantasy but a necessary function of human consciousness, the “anticipatory illumination” that allows us to perceive what does not yet exist (12). For Bloch, hope is a method: it is through envisioning unrealised futures that societies tend towards transformation. Utopia, then, is not fixed but a process of becoming. Kathi Weeks, the feminist and anti-work theorist, claims it can work alongside reform as utopian thinking helps us make demands of the present (13). Abandoning imagination, whether knowingly or not, is to resign ourselves to the concession that stasis is our only horizon.

Jameson called imagination an act “cognitive estrangement:” conceiving mock futures that recast our present as the determinate past of something yet to come. Donna Haraway’s speculative fabulation and Octavia Butler’s socially embedded futures show that speculative thought can be materially grounded (14).

On this basis, the crisis of imagination that haunts our present is not only aesthetic but political. To think utopically is to refuse the closure of history, to insist that other worlds remain possible even within the debris of the existing one.

Haraway reminds us that this refusal does not demand tidy utopias but rather a commitment to “staying with the trouble,” to imagine futures that are messy and interdependent.

If architecture has always been a drawing out of what could be, then its recovery depends on reclaiming that anticipatory impulse, not to replicate the failed grand narratives of progress, but to channel them towards collective and reparative ends.

This impulse is, to borrow from, the philosopher, Gramsci, part of the ‘struggle for a new culture.’ (15) The collective derangement of late capitalism and its oscillation between spectacle and sensuous surrender has made such spaces of radical imagination essential. Bloch reminds us that hope, when critically deployed, is a form of praxis: a demand that the future be otherwise (16). Architecture’s capacity for speculation is what links the utopian and the pragmatic, it lives in the interval between what is and what might be. The radicals of past knew this, today the same impulse resurfaces more grounded and better equipped for contemporary urgencies.

Across the continent a new generation of architects, designers and researchers, diverse in gender and geography, is redefining architectural practice. Their work, gathered through the current LINA cohort, reveals a shared preoccupation with how to build when the act of building itself has become politically, ecologically and socially fraught.

As the poles of power shift from European hegemony these projects collectively suggest that the state of architecture today is not defined by stylistic innovation or monumental ambition but by care and situated engagement. Their architecture, which emerges as a horizontally expanded field, is one of distributed intelligence and renewed humility. Porous, critical and fully acquiescent that the future of architecture will not be determined by how much we build, but by how attentively we inhabit the world.

As previous generations sought to expand architecture’s lexicon, this one expands its operation. The boundaries between architects, researchers and curators dissolve in favour of the spatial practitioner. They build new connections between environmental responsibility, historical awareness and social justice rejecting the notion of environmental sustainability as mere compliance, instead opting to see the crisis as an opportunity to reconsider the system’s politics.

What binds them is a belief that spatial practice can still produce agency, even if it no longer produces buildings in the conventional sense.

Three themes stand out:

The first of which is a move from form to process. Architecture is no longer a product but a negotiation between materials, institutions and collective will, all of which signals a refusal of the iconic and a commitment to reparation.

Secondly, the redefinition of authorship through their refusal to adhere to architecture’s historic limits as shown by the many collaborations in this cohort, whether they manifest as co-design or open-ended research projects. These projects are characterised by their distributed authorship bringing architecture into the realm of social choreography which includes residents, activists, bureaucrats, contractors and the like.

Finally, the return to the local. The LINA Fellows are all very much dealing with the specificity of place in the communities, economies and ecologies in which they intervene. The resulting work is one rooted in place. Betraying a belief that the polycrisis must be addressed jointly and severally.

Conceptually, the cohort can be grouped into: the material which investigates circularity, craft and embodied carbon, seeing architecture as fundamentally metabolic; the social which operates within systems of care, access and participation, using design as a means for social reconfiguration and the epistemic which examines how knowledge is made and shared, whether that’s through archives, teaching or new media which ultimately questions who gets to define architectural value.

Under this new regime, architecture might become a space of recuperation, a practice that gathers what the world has overlooked with a levity that looks to democratise the rhetoric (17). Cafés and infrastructures of care might be made from urban and agricultural waste, designed not to conceal decay but to live with it (18). Architecture might find circularity not as aesthetic but as manifested ethics, reusing the debris of war to question linear cycles of material and memory, cultivating resourcefulness in ruin (19).

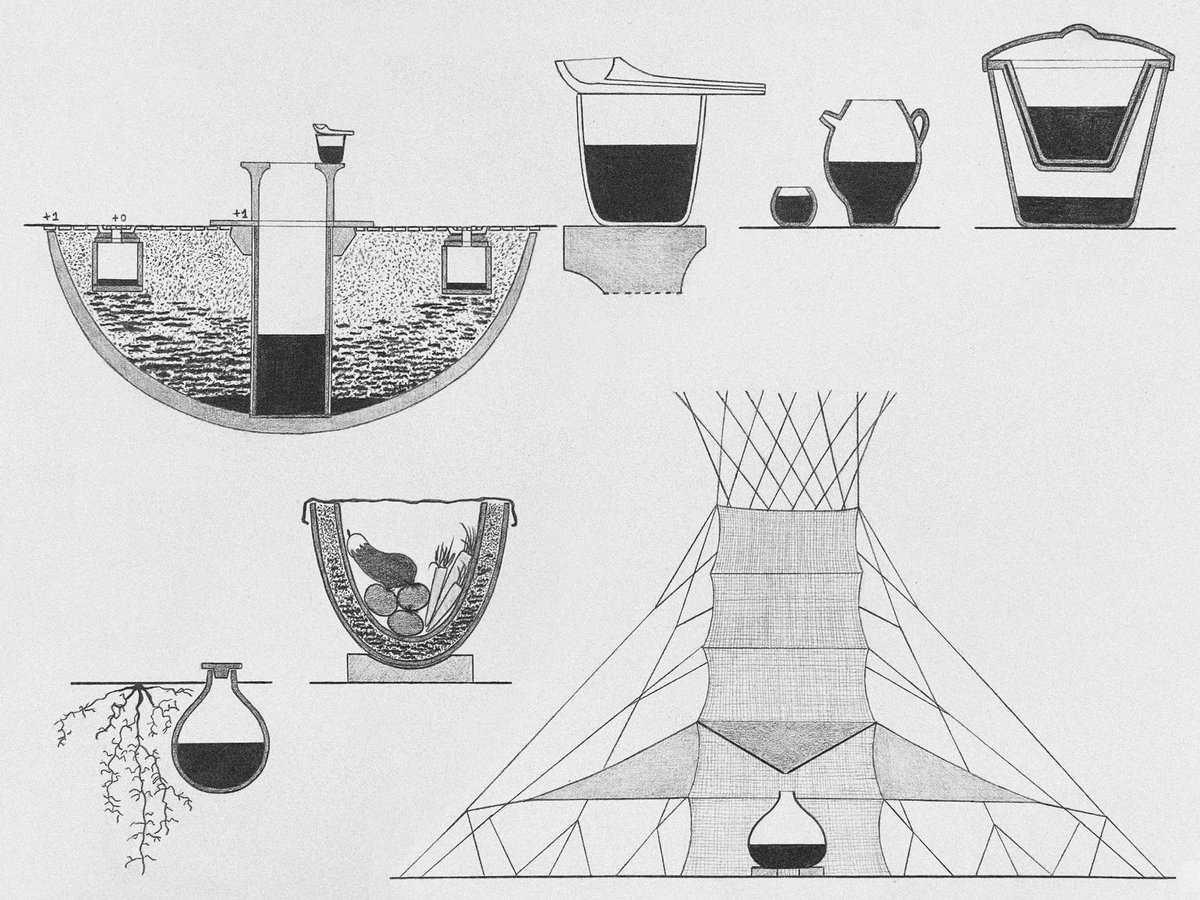

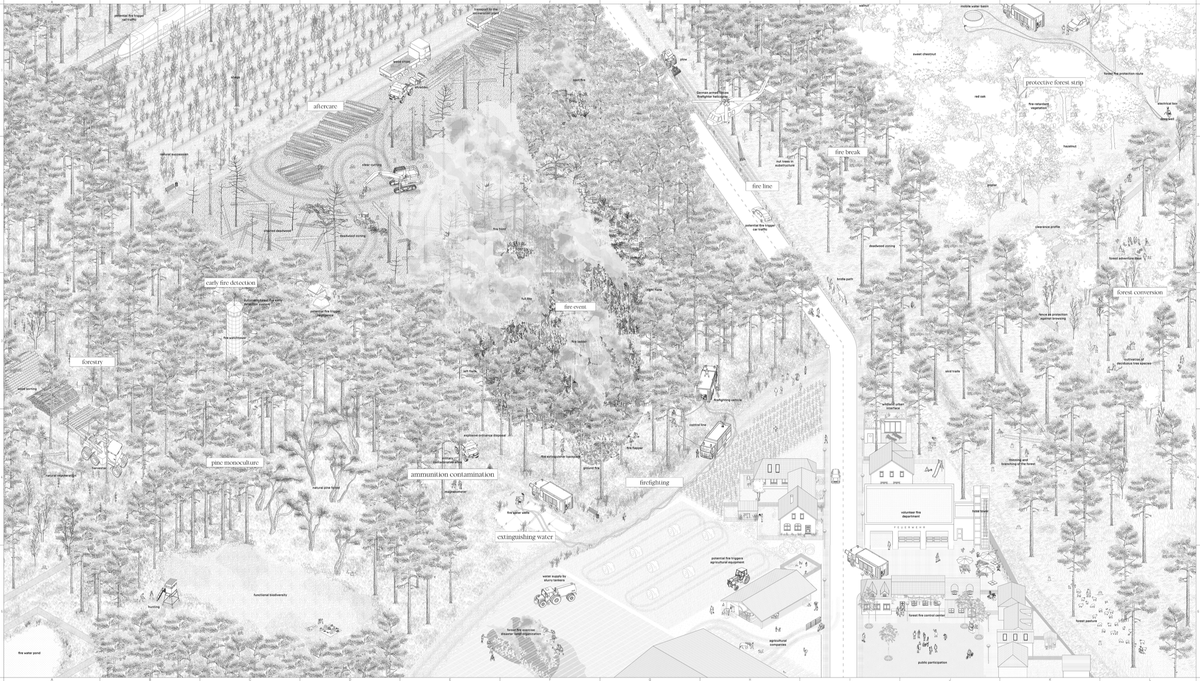

It might look to water: material, metaphor and measure of crisis learning from its fluctuations between drought and flood to redress our exploitative relationship with it (20). It might document how ecological transformation and memory intertwine, treating composting, collective gardening and community work as a regenerative practice (21). Architecture might respond to forest fires by building decentralised networks of expertise, showing that knowledge must move from the individual to the collective (22). It might learn from the forest in another sense: from non-wood projects that recognise the forest as a dynamic cultural and ecological landscape (23).

It might expose the paradox of air conditioning: the machine that both cools and warms the planet and make visible the infrastructures of climate control as cultural artefacts to highlight this paradox (24). Architecture might even turn to shade, that humble mediator, as a ground for collectivity in a warming world (25).

Architecture might redress the morphology of the historic city, inhabiting its negative spaces, encouraging adaptability rather than fossilisation (26). It might study the improvisational inhabitation of architecture not as failures of design but as a repertoire of adaptation (27). It might see potential in buildings’ abandonment, in the quiet persistence of what remains, contending with heritage that resists classification (28).

It might return to the conviction that housing is a universal right, tracing the genealogy of its betrayal through market economies and engaging systems of resistance, policy and collective action with activists, urbanists and tenant movements (29). It might confront the exploitation of architectural labour itself, turning sites of work into sites of solidarity and seeing in spatial injustice the outlines of a new politics of work (30). It might reframe domestic labour: nutrition, care, routine as the matrix of collective life, shaping environments through sustenance rather than consumption (31).

It might imagine co-designed cultural spaces that redress the inequities of schooling and under-resourced social programmes, built from what is already at hand (32). It might work against overtourism’s displacement of people to the peripheries, devising workshops and cartographic exercises that make visible the politics of the city and help communities imagine again urban centres as a field of negotiation (33). Architecture might look to the coastal wellness centres of the former socialist bloc, learning from their frankness about exhaustion, wellness and repair (34).

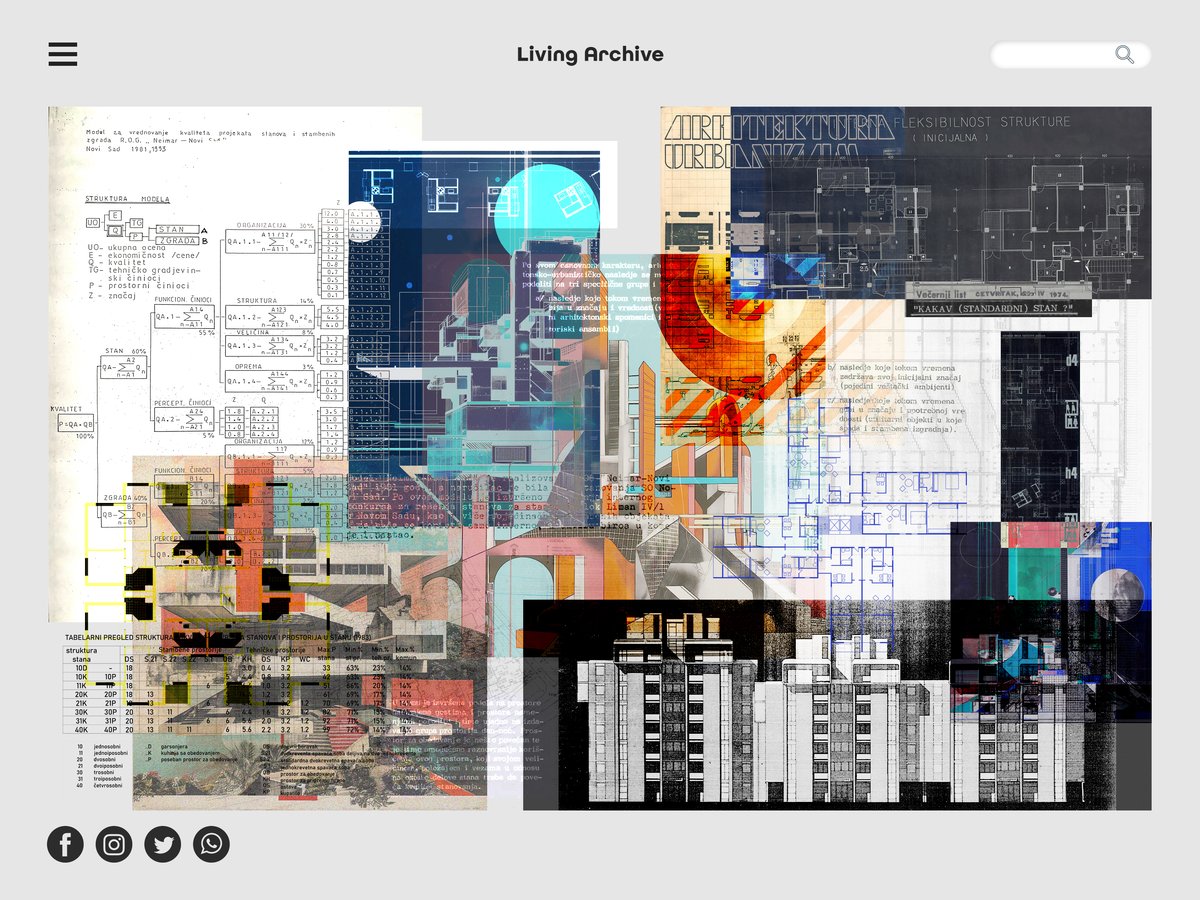

Architecture might broach the rift between the academy and life, allowing environmental, material and social dimensions coalesce into sustainable forms rooted in locality and reuse (35). It might turn to the archive as counterfactual laboratory, reconstructing the missing potential of eras ravaged by empire and extending knowledge beyond ownership (36). Architecture might extend open access to historic plans, re-animating them as mutable tools for contemporary conditions (37). It might gather spatial knowledge against imperial tendencies to control land, drawing from urban political ecology to re-imagine reconstruction as a collective right (38).

Architecture might treat accessibility as a political question, exposing the ageism and ableism embedded in European apartment typologies and proposing collective frameworks for retrofitting (39). It might reappraise maintenance as a cultural and political act, through this practice look to reinstate cultural venues made from the vestiges of the maintained (40). It might transform buildings awaiting demolition into polyvalent sites, reassessing value beyond the market’s metrics (41).

In all this, architecture may very well become a discipline of attention: to matter, to place, to others. It may become an architecture that observes and listens, staying with the world long enough to understand how it might still be repaired - designing not the world anew, but the world at last shared.

Architecture is either about buildings or it’s about people. If it’s about buildings the discipline is limited to the imagination of the people that conceive it. If it’s about people, its possibilities expand to match the imaginations of those who inhabit it.

Looking at this year’s LINA Fellows makes clear that architecture is a discipline in transition. This shift means that established hierarchies are being dismantled in order for architecture to return to relevance. These practices remind us that architecture, despite efforts to the contrary, is still able to imagine a better future. The use of this imagination is a means of steering the discipline towards forms of practice that sustain life rather than simply represent it, how architecture learns to turn towards the world again in all attentiveness, accountability and alive to what might still be made possible. The challenge ahead is to sustain that impulse and move the discipline’s centre of gravity so that, to paraphrase Angela Davis, we can make what was deemed impossible become inevitable.

The State of Architecture

The State of Architecture is based on an analysis of the applications received to the LINA Open Call, and a broader reflection on its overarching themes and their context. The text was first delivered by Ewa Effiom at the 2025 LINA Forum.

Ewa Effiom

Ewa Effiom is a London-based Belgo-Nigerian architect and writer whose work explores image culture, futurism, and mythology through the lens of space. A graduate of the Architecture Foundation’s New Architecture Writers programme, his writing has appeared in architecture and design publications throughout the world. His essay Architecture, Buildings and Conservation in MAJA was nominated for Best Piece at the 2022 Estonian Architecture Awards, following second place in the 2021 Tallinn Architecture Biennale Curatorial Competition with Adaptive Re-use. His films Eagle Mansions and Beck Road have screened internationally, from Melbourne Design Week to the Venice Architecture Biennale. In 2022 he was awarded the How To Residency at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and in 2023 became a LINA Fellow and Film Lab resident at MAXXI, where he made When One Door Opens. His most recent film was a collaboration for Theatrum Mundi’s Staging Ground Residency, exploring infrastructural change in post-Olympic Paris.

Sources

- Roy, Ananya. Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 35, no. 2, 2011, pp. 223-238

- Sassen, Saskia. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Belknap Press, 2014.

- O’Donnell, Sheila, and John Tuomey. “O’Donnell and Tuomey: ‘People Need to Know That You Are Making a Building for Them, Not Despite Them’.” ICON, 5 Mar. 2015, www.iconeye.com/architecture/o-donnell-and-tuomey.

- Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. Translated by Peggy Kamuf, Routledge, 1994.

- Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Zero Books, 2014

- Berardi, Franco (“Bifo”). After the Future. AK Press, 2011.

- Hatherley, Owen. The Ministry of Nostalgia. Verso, 2016.

- Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press, 1992.

- Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

- Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann, Grove Press, 1967.

- Kelley, Robin D. G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Beacon Press, 2002.

- Bloch, Ernst. The Principle of Hope. Translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight, MIT Press, 1986.

- Weeks, Kathi. The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries. Duke University Press, 2011.

- Butler, Octavia. Parable of the Sower. Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993.

- Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited and Translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, International Publishers, 1971.

- Bloch, Ernst. The Principle of Hope. Translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight, MIT Press, 1986.

- Ane Crisan. Urban Episodes: The Drama of Everyday Space. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- studio dreiSt. Following Material Agency. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Kateryna Lopatiuk. Circularity of the Edge. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Tiphaine Bedel. Inhabiting Water. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Jack Farman. Pioneer Species. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Carolina von Hammerstein & Vera Kellmann. Forest & Pheonix. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Max Koch. Forest Tales. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Enno Pötschke & Lisa van Heyden. Air Conditions. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Public Projects. Cooling Commons: A Shady Manual. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Spyridon Loukidis, Markos Georgios Sakellion, Georgios. Brave New Axis: Perpendicular to Athinas Street. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Fite Fuaite. Back of House. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Samanta Kajėnaitė. A Laboratory of Decay. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Pravo na grad. “Family Tree” of the European Housing Crisis. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Teimuraz Gabunia; Veriko Shengelia; Dea Khizanishvili. Changes Without Changers. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Blanka Major. Culinary Explorations Building Space of Encounter. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Sandra. KOLO. Informal Educational Space in Rural Area. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Društvo i prostor. School of Participatory Urbanism. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Galena Sardamova and Paris Bezanis. Memory Sediments: Wellness and the Black Sea Resort.

- "Al-‘ar·d". "Al-‘ar·d” Think Tank. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Valeria Prorizna. Nothing Ever Happens. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Studio After. Living Archive: A Digital Repository of Housing. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Svitlana Usychenko. Decolonial Grounds of Ukraine’s Recovery. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Nami Gradolí Giner. Might She Come Down Today? LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Natalie Novik. Acts of Maintenance. LINA Forum 2025, November.

- Andreas Stanzel. Hotel Interim. LINA Forum 2025, November.