Léopold Lambert: The State of Architecture

Having been involved in Future Architecture, which became LINA, when I first launched The Funambulist, I have always appreciated it as an organisation that decenters the way we think about Europe.

This is made obvious by the selection of the 2024 featured LINA fellows who, for a majority of them, hail from various geographies of Eastern Europe (Tallinn, Warsaw, Kharkiv, Riga, Kyiv, Budapest, Helsinki…) or even the Caucasus (Tbilisi and Yerevan). This is not merely a question of addresses on their business cards, but rather, the many diverse worlds that are mobilised in each of their work whether consciously or subconsciously. This orientation is accentuated by the fact that LINA is based in Ljubljana and that it doesn’t necessarily obey to the country’s impetus to look west towards the European Union. Although, it still does so, like when Slovenia built a wall on its border with Croatia, which I was able to document many years ago.

That’s why I appreciate that LINA looks and turns towards East, be it Kosovo, Georgia, Ukraine, Albania, Romania, and to a place that is geographically not East, but is “East” to my heart, if I may say it like that: Ireland. I’m grateful for this clear recentering or decentering of Europe as we know it, especially with the self-importance of colonial Western Europe. It’s also important to me that we’re in Sarajevo. I was between six and nine years old during the siege and Sarajevo was mentioned every day and echoed constantly in my young mind. It has stayed with me to this day. When I was lucky enough to visit Sarajevo for the first time 10 years ago, it had a very strong impact on me. Returning to it now, I still feel a connection to it - more on that in the second part of the essay.

In settler colonies, some people do what we call a land acknowledgement. Personally, I’d like to make a time acknowledgement by reminding us all that while we are here at the conference, Israel is continuing its genocidal campaign in Gaza and South Lebanon.

I invite you to bear this in mind because here in Sarajevo, we’re just a few months away from the 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocidal massacre. Acknowledging the time we're in is something we ought to do more often. To conclude the introduction, I’d like to emphasise that I appreciate this particular commission by Matevž Čelik- to evaluate the state of architecture. I interpreted this commission in a very subjective way as what the 15 last years have meant for architecture.

I warn you, it starts with a bunch of white men, but it will get better along the way! In no way does this mean that women of the Global South or racialised women in the Global North have not simultaneously worked on similar questions that I’m delving into today. What it means rather is that they were not given access to the infrastructure of knowledge diffusion.

My first visit to Palestine in 2008 is a very important aspect of my training. It was an epiphany – an odd word, surely, but an apt one nonetheless. I realise the inherent obscenity of a white European suddenly realising the truth about something, but it has been exactly that. In addition to the encounter with the Israeli settler colonial machine, I realised the absolutely crucial role that architecture plays in it.

It was around that time that I started a small blog with a couple of friends (Martin Le Bourgeois and Martial Marquet) titled Boiteaoutils, which became the ancestor of The Funambulist. Boiteaoutils was a toolbox with which I tried to write about the political dimension of architecture and, very importantly, the political complicities of architecture.

I started defining architecture as a discipline that organises bodies in space with all the political implications that can have.

In 2010, I started The Funambulist as a blog, mostly to host my clumsily-framed written pieces, which allowed me to take my place in a small community of people who wanted to think about similar topics. The small community I’m referring to included LINA members César Reyes and Ana Dana Beroš. It felt lonely at the time because I was still in architecture school and it felt like hitting a wall. Not so much a wall of antagonism or direct conflict, but a wall of indifference. Without wanting to skip to the conclusion of this text, I’d like to emphasise that the state of our practice has changed for the better.

In 2010, César Reyes and Ethel Baraona Pohl were kind enough to accept a proposal to publish my first book titled Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence, which addresses the fact that architecture is inherently violent, and that this violence is always instrumentalised by a political regime.

These political regimes were either settler colonialism, hetero-patriarchy, ableism, structural racism, anti-Blackness, and so on. But this book was perhaps more connected to the question of Palestine.

In 2015, The Funambulist became a bi-monthly magazine in which we asked ourselves these same questions. Instead of trying to politicise the architecture community, something I still tried to do to a certain degree, it tried to approach a politically engaged community and ask them to think about space. I don’t want to continue describing my work, but I’d like to reflect on the last 15 years of architecture. To do so in Sarajevo, for me, is also very important, I think that Sarajevo has something to do with where we are today in architecture, perhaps worldwide.

Some of the LINA fellows were born in the mid 90s, perhaps even later, and they don't necessarily realise what Sarajevo represents for countless people.

On 25 August 1992, the great library of Sarajevo was shelled by the Serb paramilitary groups from the hills; an event that has contributed to rethinking the way cities and civilian infrastructure were targeted by aggression.

I’d like to mention Bogdan Bogdanović, the former mayor of Belgrade, who re-coined and emphasised the word urbicide – the same word that we’re using right now when we talk about Gaza. Or how Lebbeus Woods from the US influenced an entire generation of politicised architects in the West. His vision was built on rethinking how to rebuild a city like Sarajevo. Of course, what Woods imagined, Sarajevan architect Ivan Štraus did. What I describe reaches far beyond the 15 years I set out to present, but I wanted to contextualise Sarajevo as one of the places of genesis for my thinking. And of course, although Sarajevo is definitely not how Europe thinks of a European city, it does remain a European city, and we ought to decenter from it. Such a genesis can also be sought elsewhere in the world and in Palestine in particular, with the Riwaq project in the early 90s, which aimed to renovate and restore Palestinian heritage buildings that had been destroyed. Riwaq is a gesture of political resistance.

But now, let’s really start this 15-year retrospective, and jump into 2004. The book Cities, War and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics by Stephen Graham was, again in my own subjective way, one of the first books I’ve read that really addressed the urban condition of colonialism and urban condition of geopolitical invasion and wars. It was a key book that influenced my generation, and perhaps the generation before mine as well. And even more so, the book by Eyal Weizman and Rafi Segal titled A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture. They also tried to realise an exhibition that was completely censored by Israel. The book itself documents the architecture of Israeli colonies in the West Bank. Later on, in the book Hollow Land, Weizman builds an entire theory of the architecture of violence in the specific context of Palestine, but this theory could be applied to other places as well, and by doing so, Hollow Landbecame a groundbreaking moment in architecture theory.

Similarly, Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti (along with Weizman) started the Decolonising Architectural Art Residency in 2009. I remember thinking: “Wow, this is literally the most interesting thing in architecture right now”; where architecture students and architecture graduates would meet in Palestine and workshop for a week, all this greatly influenced my work.

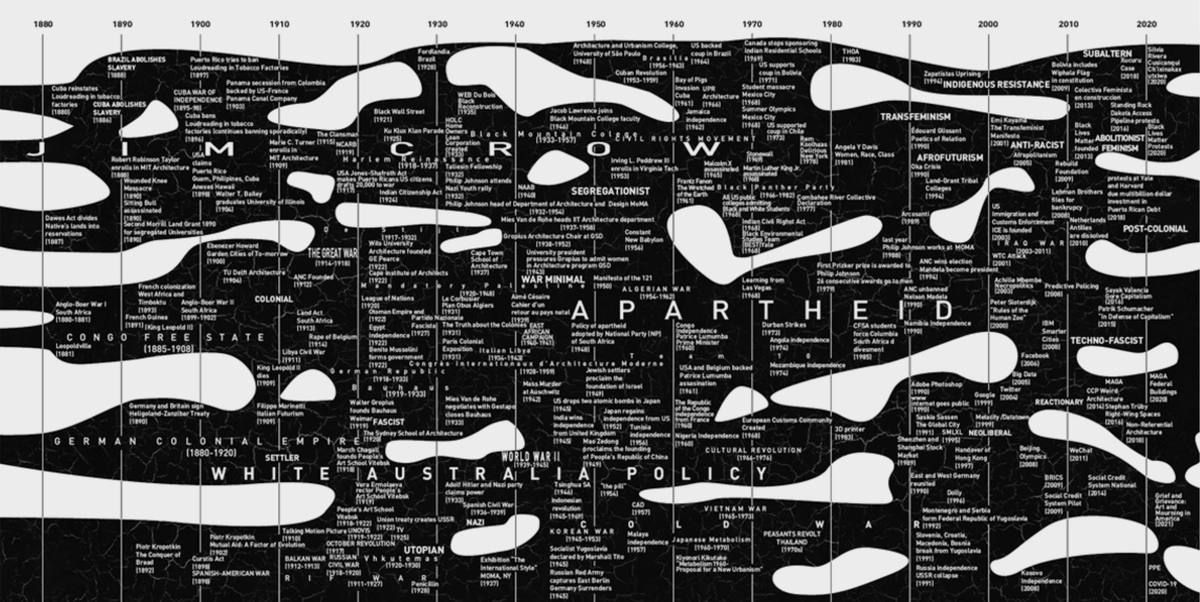

Of course, to think about the history of architecture in a vacuum is totally ridiculous.

In the last 15 years, we can identify a certain number of world events that really impacted the way we think about the world in general, and therefore how we think of architecture.

There was the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions, as well as various other movements in North Africa, the Gulf, and the Levant that are instrumental in the rethinking of the world. The impact of these events has translated to architecture, I can illustrate this by mentioning the work of my friends, such as the initiatives of Ahmad Barclay and Dena Qaddumi who write for Arena of Speculation, and Mohamed Elshahed’s Cairobserver.

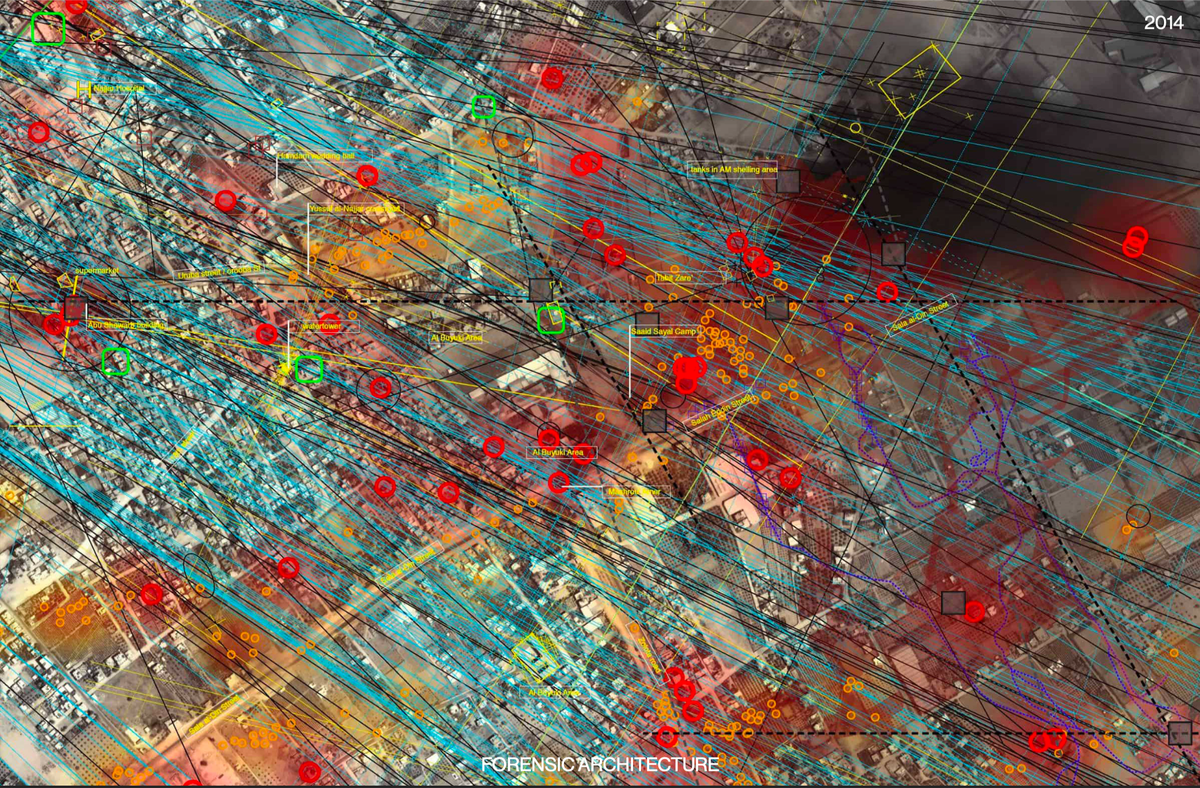

Eyal Weizman continued his trajectory with the book The Least of all Possible Evils, in which he wrote a chapter on Gaza based on a lecture titled Forensic Architecture. The latter gave its name to a collective formed in 2011 that we all know today. The collective uses architectural skills and tools to investigate colonial and imperial crimes. If we look at a photo of their first investigation (below), you can see how much their work has evolved. In the summer of 2014, during the last massive bombardment and invasion of Gaza led by the Israeli army, Forensic Architecture also used its method to describe the murderous violence at play.

When The Funambulist magazine started, I decided to include a dedicated section for architecture or design students, which perhaps showed the changing zeitgeist in architecture schools and the growing politicisation of students looking into the north of Ireland, the US invasion of Iraq, Algeria... Speaking of students, I’d like to mention the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg created and directed by Leslie Lokko with the aim of decentralising architecture education – all while some of us were still looking up to Britain, the US, Canada and the Netherlands as key places to learn about architecture and how to reflect on it. However, what Leslie created at the Graduate School of Architecture, helped by amazing instructors such as Huda Tayob and Sumayya Vally (and many more), changed the entire way of thinking about architectural education and, in particular, centering the personal life of many Black and non-white female students in South Africa.

They were building on the heritage of the apartheid struggle and this continues to be in many ways a very important site in which architecture is being reconfigured.

In 2017, the book titled Architecture of Counterrevolution by Samia Henni was published. Henni was drawing from her PhD at ETH in Zurich. This book has been instrumental to me, and I see parallels with Henni's breakdown of French colonialism in Algeria with what Eyal Weizman’s research on Palestine.

It was around this time that Future Architecture, the predecessor of LINA, started with projects such as Resolve (Akil Scafe-Smith, Gameli Ladzekpo, Seth Scafe-Smith, Vishnu Jayarajan), Aman Iwan (Debray Côme, Jaquet Michel, Wardak Feda, Szlamka Youri), Curriculum Revolution by Charlotte Malterre-Barthes in collaboration with Dubravka Sekulić, Afro-Futures in European Enclaves by Menna Agha, Mario Barros and Diogo Henriques.

In 2019, the Chicago Architecture Biennial was held as well. I’m not sure whether the Biennial itself produced anything new, but it was a collection of very interesting projects done at that time. More specifically, Settler Colonial City Projectby Andrew Herscher, Ana María León, and the American Indian Center that brought attention to the stolen dimension of the land on which the Biennial, but also the whole North America, was built on.

Inspired by the massive movement in Standing Rock against the North Dakota Access Pipeline, this was a key moment to rethink settler colonialism in the US.

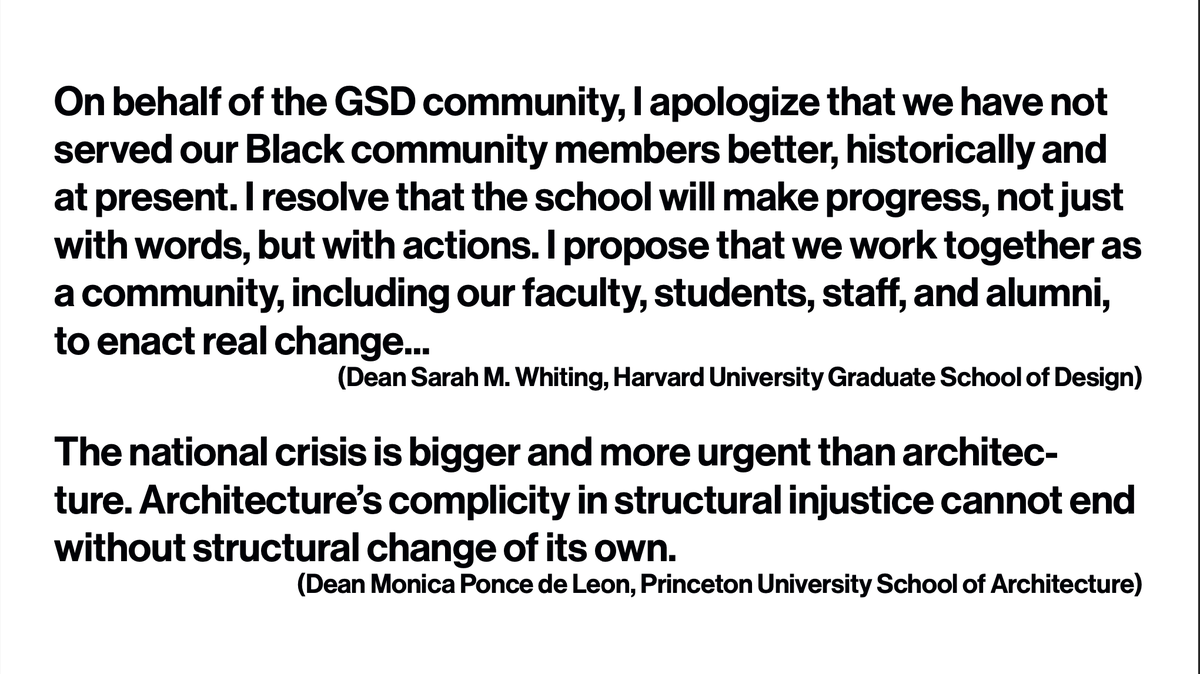

In 2020, at the Funambulist, we aimed to spotlight 16 young architects whose work actively engages with issues of anti-Blackness, settler colonialism, and patriarchy – four of them were graduates from the Graduate School of Architecture of Johannesburg that I just mentioned. This coincided with the Black Lives Matter uprising, also in 2020. I usually don’t want to centre the US in its way-too-influential epistemological production, but truly, this movement had an incredible impact on institutions such as the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Princeton University School of Architecture. Although I don’t trust the performative statements that were issued by their deans, the fact that they were forced to make them was very interesting and it had a profound impact on the evolution of the discipline of architecture. I think that this is also the moment when the long architectural practice of Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz Garcia started to be celebrated too.

Getting closer to today, the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale The Laboratory of the Future curated by Lesley Lokko was an interesting moment, I think. If I had to put forward one of its most powerful works, it would be The Uhuru Catalogs by Thandi Loewenson. And with this, I’d like to move back to Palestine with the project by Elias and Yousef Anastas titled Wonder Cabinet, which is a designed and curated space in occupied Bethlehem that is built to look at the massive Israeli colony in front of its windows. This project is an incredible example of making space in an occupied territory.

To delve back into the LINA territory, I’d like to highlight the work of LINA fellows, namely Margarida Waco, who was part of The Funambulist between 2018 and 2020, and Meriem Chabani.

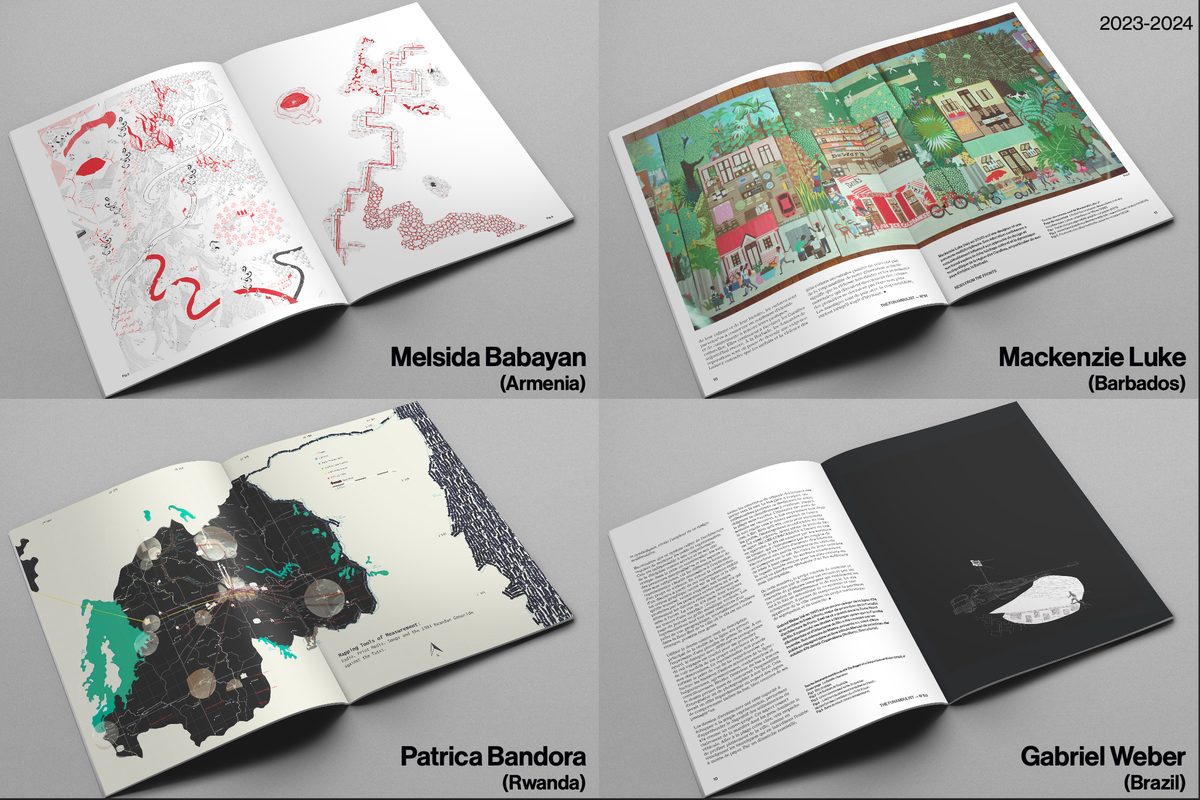

Meriem and I have been in conversations for years, and we now share an office between New South and The Funambulist. We recently went back from publishing architecture student projects, but this time, without bringing attention that they are created by students. This is how we published researches by Melsida Babayan in Armenia, Mackenzie Luke in Barbados, Patrica Bandora in Rwanda, Gabriel Weber in Brazil, Yeh-Ting Li in Taiwan, and Nasrynn Chowdhury in Burma/Bangladesh/Britain.

I’d like to conclude this essay with the state of architecture in 2024: we noticed a massive suppression that we've seen in the key sites of architecture education, such as at the Columbia University, where the New York Police Department besieged the University and destroyed the solidarity encampment with Palestine on campus. Similarly, some of you might have seen the sort of press campaign that was led against some of my friends, including Samia Hanni, and myself, which led to the ETH Zurich to cancel a talk I was supposed to give on the architecture of settler colonialism in Palestine initiated by the university students. ETH cancelled and censored that talk, but at the end of the day, a talk that would have gathered something like 40 students, but by cancelling it, and thanks to the solidarity of many people, I got to speak about architecture’s complicity in Palestine to no less than 800 people assembled both behind their screens and in alternative spaces in Zurich.

As I mentioned earlier, my first book’s subtitle was The Impossibility of Innocence.

I think it's never been clearer today that there is no longer any innocence being afforded to any of us.

This talk at ETH was organised by students and these two individuals had the entire infrastructure of their university antagonising them and censoring them. Students in schools nowadays are already engaged in very strong politics and we, individuals outside of the schools, need to be there for them to support them. So, in this particular moment, we're living in a time of great violence being raised against us. However, looking back to just 15 or 20 years ago, I remember feeling so alone, faced by indifference, even though that might not have really been the case. Today, I see so much amazing research and projects coming from new generations, which gives me a great feeling of optimism.

Looking at the type of projects created by the 2024 LINA fellows, it is obvious that many of them have been influenced by parts of this small history I tried to outline here. Whether they are fully aware of this influence or not is almost irrelevant.

What constitutes a truly impactful contribution to a discipline goes much beyond the simple realms of the citational: they create new epistemologies that are almost atmospheric in the way they influence us all.

Some of these projects share common questions, such as the legacy of Soviet-induced architecture in their cities, or the centering of housing as the crux of a space of dignity for structurally marginalised communities. With LINA, they can form together a constellation of support for each other. I started by stating my appreciation that this constellation is anchored in Eastern Europe; what I can wish the best to them would be for the creative proliferation of ideas and political engagement occurring outside the limits of Europe (i.e. the large majority of the world) be also of great influence on their development. Thank you very much for your time.

The State of Architecture is based on an analysis of the applications received to the LINA Open Call, and a broader reflection on its overarching themes and their context. The text is a transcript of the lecture, delivered by Léopold Lambert at the 2024 LINA Conference.

Related fellows