Satoyama or the watergarden

Ludivine Gragy is a landscape architect working on various scales of territory. In her projects Plants, Soil, Water & Stones cohabit in order to enable ecosystems to grow.

Her practice is driven by experimentation and the maintenance of a close link between creation, realization and its cultivation over time. She founded her Berlin (DE) based studio in 2018.

During her working process, digital and analogue tools come together to enhance the optimization of natural resources. Considering the specificity of the site as key for the project development, she tends to create living spaces for all species. After graduating from the National School of Applied Arts ENSAAMA in Paris in 2006 and from the National School of Landscape Architecture ENSP in Versailles in 2010, she has gone on to work throughout Germany, Japan and Switzerland. Between 2011 and 2018, she has gained professional experience in offices such as Kuhn Landschaftsarchitekten and atelier le balto, in several aspects of the landscape architecture discipline.

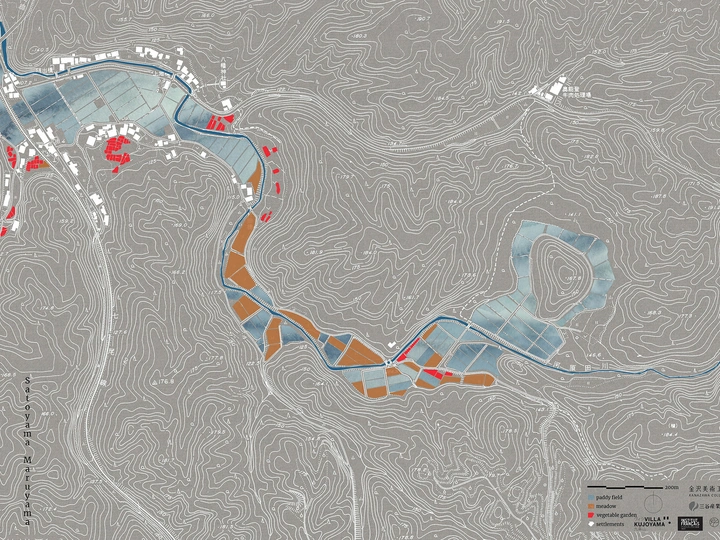

Satoyama 里山 is a rural socio-ecological system including forests, rice paddies, irrigation networks and settlements. In Japan, this productive landscape is adapted to the climate and the geomorphology of the territories. It mirrors the cyclical and close relationship between human beings and their original habitat. The sustainability of this land-use mosaic relies on community’s ability to manage respectfully their environment and on the transmission of specific knowledges. Human beings, plants, animals and soil are interconnected, and the natural resources of the site are harnessed to foster community life. The introduction of fuel and chemical fertilizer in the1960s has contributed significantly to the erosion of these systems. Today, as they are disappearing, the question of their future arises.

In Fall 2022, I researched these fragile ecosystems looking at the role of water. The water cycle repeats itself every year to irrigate crops and change its environment by modifying its vegetation and wildlife. It is expected that over the next decades water will become a scarce resource in Asia and on the other continents due to climate change. There is an urgent need to reconsider our way to design living areas to make them habitable. How can the water cycle and its management as a structural element be integrated into the design of rural and urban areas?

An ecosystem doesn’t work without considering the notion of cycle and interdependency. Managing resources and waste needs to be approached from the human scale, considering the environmental capacity and natural resilience of each region specifically.

What if we learned from this organic land structure to plan our future cities?

By creating ‘symbiotic’ ecologies, we don’t only reduce impacts but also generate new visions and long-term regeneration. As new aspects of planning seem to be emerging, we aim to change reflexes by giving design an ontological dimension that can change our way of being and acting.