Room for Yiddishkeit

I am an architect by training and a researcher by orientation. In recent years, I have been working within an academic architectural environment where I focus on Soviet architectural typologies and editorial work. My initial interest in architecture was shaped by its capacity to organise space, but my perspective has since shifted toward a more humanistic optic. Increasingly, I find myself drawn not to form as such, but to relations—between the body and its environment, between labour and the built world, between language and space.

My research inhabits the intersection of history, architecture, and feminist theory. I arrived at this orientation gradually, through an accumulation of questions and unease. What compels me are those forms of architectural experience that are not codified into design, but instead persist in writing, in habit, in narrative. At present, I am interested in working with women’s texts from the late 19th and early 20th centuries—written predominantly in the context of the Russian Empire and the early Soviet Union. I am drawn to the way these texts register feminist discourse through the articulation of thresholds: between private and public, duty and punishment, body and norm. I want to explore what these descriptions allow us to extract today—particularly in terms of rethinking the architectural conditions that might sustain equity and a politics of care in space.

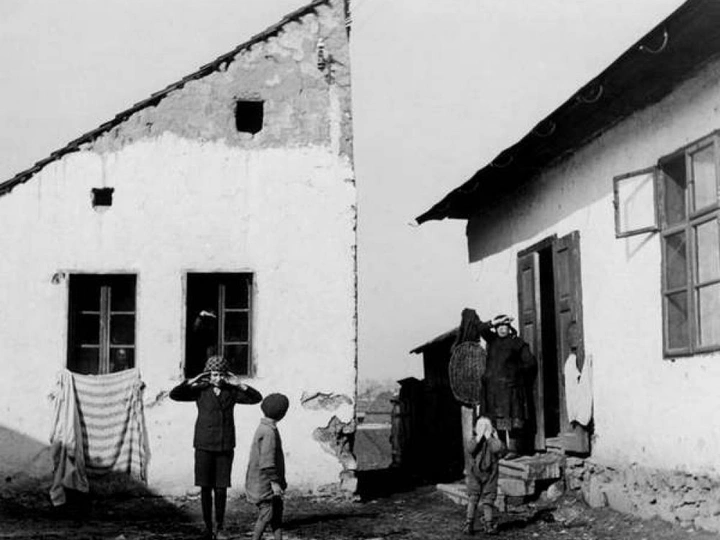

This project seeks to reconstruct a set of spatial practices—rooms, rhythms, materials—through which diasporic Yiddish culture, and in particular its women, articulated forms of intellectual, political, and affective life. It begins from the premise that the history of Yiddishkeit, often treated as metaphor or nostalgia, must be read through architecture: not only as built form, but as infrastructure of relation, care, and transmission.

The focus lies on the rooms of the Yiddish press—especially as shaped, read, and sustained by women at the turn of the 20th century. These rooms were neither private nor public. They were shared spaces: kitchen tables, boarding houses, letters read aloud, serialized texts cut and passed on. They were rooms of world-making. Through close readings and spatial reconstruction, the project seeks to understand how these environments supported epistemologies of resistance—against patriarchy, assimilation, and later: nationalist erasure.

Between 1903 and 1921, pogroms across the Russian Empire systematically targeted Jewish communities. A generation later, between 1933 and 1945, the Holocaust annihilated not only the people, but the worlds of Yiddishkeit. Women’s voices—already precarious, often excluded from institutional memory—were doubly silenced. This project understands spatial practice as a means of re-entry: of tracing what was lived, and what was interrupted.

Room for Yiddishkeit will evolve into a spatial-archival format: possibly an annotated cartography of vanished reading rooms, or an immersive reconstruction of domestic-public architectures of care. I see this not as a fixed proposal, but as a process that can take shape in dialogue with LINA members.

To dwell in this room is to propose a cultural continuity not grounded in territory, but in relation, transmission, and the multilingual materiality of survival.