The Shape of Resilience

My practice explores the relationship between people and places, uncovering the forgotten stories and concealed emotions held within specific sites. I am particularly interested in how physical environments hold memory, whether through material, form or silence, and how design can act as a tool to uncover and reimagine these narratives. I create immersive installations by combining raw, natural materials with industrial elements that represent the current era. These installations encourage viewers to reconsider concepts of invisible connection, memory, and survival.

Over the past two years, I studied Contextual Design at the Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands, where I explored how materials can carry embedded narratives and social meanings. I begin each project by exploring the cultural, historical, and emotional layers of a site. Then I collect local resources that reflect its physical qualities. Through hands-on experimentation with resin, plaster, metal, and fabric, I developed a deeper understanding of both technical craftsmanship and conceptual storytelling, learning how materials can be both subject and medium.

Before starting my MA studies, I worked for four years as a spatial designer in South Korea. I led projects of various sizes, ranging from interior and lighting design to brand installations and exhibition. These professional experiences taught me how to balance practical constraints with creative vision, and how to collaborate with clients, artisans, and builders to bring ideas into physical form.

Beyond my role as a designer, I am also developing my position as a curator, mentor, and storyteller. I aim to organise exhibitions, workshops, and collaborative events that reflect my belief in design as a shared and socially engaged act. I think of spatial design as a means of not only expressing myself or solving problems, but also of asking difficult questions, opening up spaces for dialogue and fostering empathy within communities.

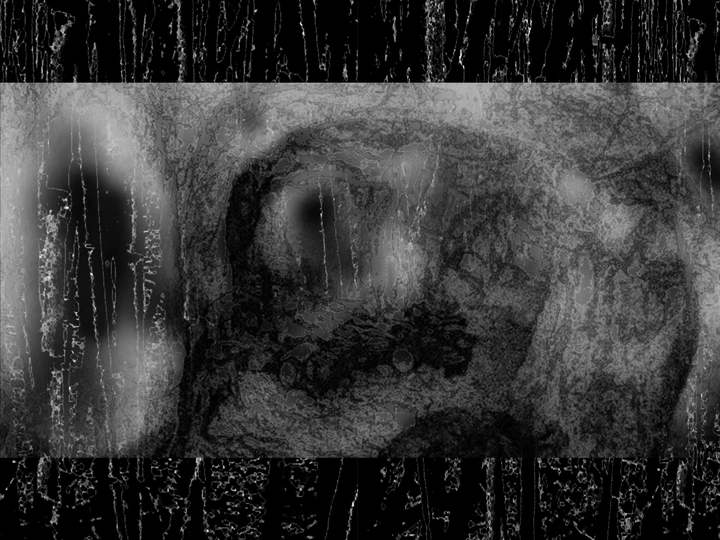

While underground tunnels are often seen as military sites, I reconsider them as spatial expressions of resistance, survival, and autonomy. Through an autoethnographic study of the tunnel dug by my family in South Korea during Japanese colonisation and later used during the Korean War, I reflect on how civilians created hidden, self-built shelters without institutional support, often in direct opposition to state power. Rooted in the natural resilience of bamboo, this place became not just a physical refuge but a symbol of community solidarity and unrecognised human dignity. Such spaces resist the demand for visibility and offer a model for how opacity can protect life in moments of systemic crisis.

Contrary to dominant narratives in the world, where tunnels are viewed through militarised Cold War ideology, this project frames them as sacred, subaltern architecture—part of a broader, global history of underground refuge. From prehistoric caves to wartime shelters, humans have used the invisible place not only to escape violence but to reclaim autonomy. Even today, global crises, whether political persecution, war, ecological collapse, or authoritarian control, continue to push individuals into situations where formal protection fails, and improvised hidden spaces become essential for survival. These personal tunnels are rarely documented or preserved, yet they persist across borders as quiet acts of resilience. Many such spaces have been recently uncovered, often misunderstood and neglected.

Interpreted through concepts like the “undercommons,” the tunnel is not a space of organised revolt, but rather a zone of opacity and survival that challenges the dominance of violent light, transparency, and control. In a world where visibility is linked to productivity, legality, and surveillance, this proposal calls for hidden spaces to be recognised as essential counter-architectures.